Throughout my career, although I built many software solutions in an effort to solve a number of what I viewed as unjust social structures, no self-inflicted wound of society consumed me more than the seemingly rampant destruction of authentic community. How could we, as beings who derive so much joy from communing with others, have created a society where such authentic being-with has become so difficult?

It was during an early product meeting at one of those companies where I had what I considered a breakthrough in understanding this problem. During these meetings we would spend hundreds of hours trying to understand how communities work and how we might build software worlds that could promote human connection. At the end of what felt like another fruitless discussion, I erased all our diagrams and workflows from the whiteboard, and instead drew four names.

These names were of the people whom I had become friends with over the past few years. I then began to simply tell my team the stories of how we had met and how our relationships had developed. The first thing we discovered is that I didn’t really share that many interests with them. Given that we were often thinking of building communities of interest, this was an important insight.

The more shocking thing was that when I first met each of these people, I didn’t even really like them. What had actually happened was that my wife had developed relationships with their wives. Because of this, I had been forced repeatedly into social situations with these guys. I didn’t really want to do this, but the social situations were benign enough, and ultimately, I didn’t really have a choice.

What happened through these safe, repeated interactions was that we began to develop some history together. What had at first blush appeared as irreconcilable differences, became the quirks that made them who they were. Interactions that had felt forced, now felt natural. Instead of dreading these get-togethers, I began to look forward to them and even encourage them. In other words, we had become friends.

As I went deeper, back into my life, I saw a similar pattern. It wasn’t that I had repeatedly stumbled upon people who were perfectly suited to me. It wasn’t that there had been the perfect social preconditions for community development. Throughout my life, it was simply a matter of safe, repeated interactions that had made the magic of human connection bloom.

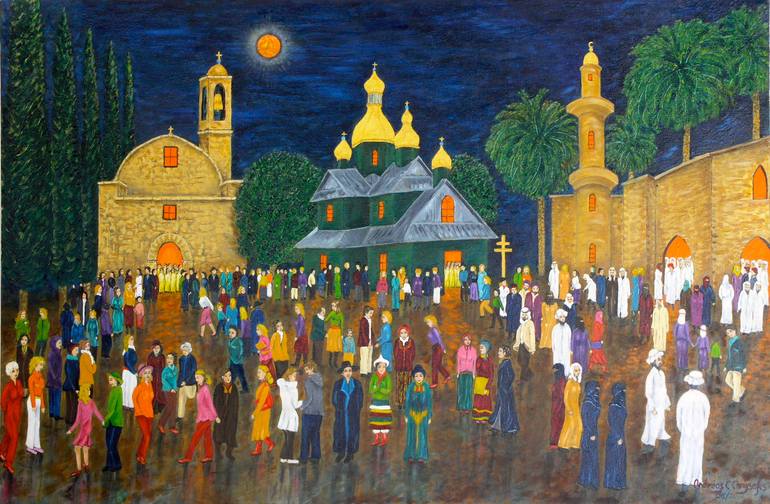

Religious institutions are dying in the Western world. Modern cities in the west are littered with the corpses of abandoned churches and synagogues that are either being destroyed, converted into commercial enterprises, or visited primarily by tourists exploring their architectural history. I don’t think this is because modern humans suffer from too much community. I don’t believe it’s because secular equivalents have risen to the occasion of helping us build the deep and meaningful relationships so essential to human happiness.

I believe the biggest issue with these institutions is that what gave them their vitality was that they were institutions of faith. In fact, those religious institutions that continue to grow are explicitly those who practice a more fundamentalist or evangelical breed of their religion–in other words, those whose members actually believe.

The problem is that it’s becoming increasingly intellectually untenable in a world that has learned so much about itself over the past few hundred years to base one’s core beliefs on stories written long ago by primitive people. We might be willing to visit these ancient texts, just like we visit ancient ruins of all societies–because some truths don’t change and sometimes the new obscures what was clear to the old. But asking a modern human being to believe the details are actually true? That’s more than the modern mind can bear.

Will Thanatism be able to build new, believable religious institutions?–a lofty goal indeed! I don’t know that any faith will be powerful enough to drag our overworked bodies out of bed on a weekend morning anymore. If it were, I suspect those mornings would be greeted with the same skepticism of any church-going dad who had to miss Sunday football or crusty-eyed kid dragged to Sunday school in the good old days.

Having said that, Thanatism doesn’t require any suspension of our ordinary ways of thinking to believe. It does possess the ability to transform the believer, just like the faiths of old did. And I do remember attending religious services as a true believer. They were different and possessed a vitality that’s difficult to explain.

And even if a place for Thanatists to gather doesn’t induce the religious fervor of the past, it could still perhaps serve as a place for safe, repeated interactions, a place where ordinary people could take a moment out of their week to join with others to reflect together on this conundrum we all find ourselves in called life. Perhaps we might even sing some songs together and share a meal.

Should Thanatism provide such a simple place where people could gather together and feel less alone for a bit, should we be able to rediscover a belief which can be common to us all, the kind which, when felt in the past, in other forms, has created places of genuine care, then we shall know we have truly arrived. For Thanatism is not a philosophy. It is not an argument. Rather, Thanatism is a faith, a faith for ordinary people to circle around and collectively remember that we, broken humans, are all that we have.